My Approach to Evaluating Faculty Applications

As a faculty member at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF), I am often asked about my approach to evaluating faculty applications. In writing it out, I not only clarify my thinking, but also provide transparency about how one faculty member evaluates applications. Additionally, by sharing this, I hope to get feedback to help improve my own process for evaluating applications in the future.

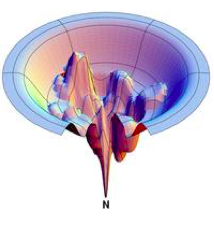

Evaluating faculty applications, in my view, is akin to the process of protein folding, as described by Levinthal’s paradox. Levinthal’s paradox suggests that it would be virtually impossible for a protein to achieve its functional structure by exhaustively exploring every possible conformation due to the sheer number of potential configurations. Instead, proteins navigate through a funnel-like process, where a sequence of favorable local interactions steers the protein toward its final, folded ensemble. When I evaluate faculty applications, I adopt a similar approach. I don’t undertake an exhaustive examination of every single detail of all applications. Instead, I employ a funnel-like process, starting with broader criteria, then progressively narrowing down to more specific aspects of the proposed research program. I strive to do this without resorting to traditional markers of prestige such as the reputation of the journals where they’ve published or their academic pedigree. This process guides me toward the most promising applications that resonate with me both scientifically and in terms of shared scientific values.

The first step in my evaluation process is to review the Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) statement. Based on other published rubrics , I assess the applicant’s awareness and involvement in DEI initiatives. I’ll also look over any teaching or mentoring track record as part of this, recognizing that not everyone has had the chance or environment to fully engage in these activities. This is a critical step for me. If an applicant does not demonstrate a strong commitment to DEI, I do not proceed further with their application. This initial screening takes less than five minutes per candidate and typically eliminates about half of the applicants.

Next, I turn my attention to the research statement. The opening page (and especially the opening paragraph!) is crucial here. I look for a clearly articulated problem or a set of problems that the applicant intends to address. If the scientific problem statement, its significance, or the applicant’s approach to solving it are unclear to me, I do not proceed with considering the candidate. This step takes less than two minutes per candidate and usually eliminates another half of the remaining applicants.

For the remaining candidates, I undertake a thorough review of the entire research statement and cover letter. I study the applicant’s key preprints and papers to familiarize myself with their specific scientific questions and approaches. Interestingly, many of the faculty members I’ve been involved in hiring at UCSF had not yet published their major work in a peer-reviewed journal at the time of their application. This is not a deterrent for me; in fact, I embrace preprints wholeheartedly. Preprints provide an open and immediate insight into a researcher’s latest work, and I am fully capable of evaluating them on their own merits. However, what I find less favorable are “confidential manuscripts in review”. Because these do not offer me the same level of transparency as preprints, I won’t review them as part of the application. Including such “confidential manuscripts” demonstrates a disconnect with the open science principles that I value in future colleagues.

During this stage, I also try to evaluate how successful they have been in making progress on key problems in prior career stages by scanning letters of reference and scanning additional papers by the applicant (and often in the field of the applicant).

I also want to clarify what I look for in reference letters, even though they are a minor factor relative to the research proposal and papers of the applicant. It’s common for every applicant to be described as “the best person who has passed through the lab in years,” so overall praise isn’t the differentiator for me. Instead, I focus on three key things:

1 - Context for the scientific barrier the candidate overcame in their prior work.

2 - Discussion of how the candidate’s FUTURE work will differentiate from the thrust of their current lab.

3 - Corroborating data on teaching, mentorship, and outreach.

Letters can add depth to these three dimensions, but rarely detract from them. While it’s not a strict requirement, a well-crafted letter that resonates on these three issues can be immensely helpful in painting a comprehensive picture of the candidate.

This overall step of evaluating the research statement and papers (with a scan of letters of references and other papers) is time-intensive, taking approximately 20 to 40 minutes per candidate. However, this is the point where I decide if a candidate should be evaluated by the entire committee, generally nominating about 10-15 candidates.

At this point, I also get the short list of other members of the committee. Some of my colleagues may weigh other factors such as the prestige of journals where the applicant has published, their academic pedigree, or the likelihood of securing funding. This diversity in evaluation criteria is a strength of a committee approach, provided we are all aware of and acknowledge our biases. We typically get about 100-300 applicants in a cycle, but there is usually a significant overlap in shortlists. Generally, the committee process leads to a shortlist of ~25 candidates.

The next step involves a deeper reflection on each shortlisted application. I spend an additional 30 minutes per application, contemplating the fit of the research statement with our institution and gauging my excitement level about the proposed research. I again consider the DEI and teaching/mentoring efforts. My aim is to identify 5 to 7 applicants that I am extremely enthusiastic about, 10 applicants that I am open to learning more about if other committee members are sufficiently enthusiastic, and 5 to 10 applicants that I am skeptical about but am willing to be convinced by other committee members.

Finally, we (the hiring committee) engage in a comprehensive discussion and ranking process. Each committee member presents their shortlisted candidates, and we collectively rank them for zoom and/or on-site interviews. This process tries to offer a balanced assessment of each candidate, helping us identify the most promising faculty members for UCSF.

In conclusion, my approach to faculty application evaluation is designed to be rigorous and thorough, while being efficient and minimizing proxies of prestige like journal name or institution. I’m cognizant that I have my own implicit and explicit biases, but what is outlined here is a reflection of how I try to identify candidates who not only excel in their research but also share our values. I believe it’s important to share my process, not as a standard, but as an example of one possible approach. I encourage anyone serving on a hiring committee to outline their own unique criteria and detail the process they use to arrive at a shortlist.

Thank you to Prachee Avasthi, Zara Weinberg, Willow Coyote-Maestas, Stephanie Wankowicz, Chuck Sanders, Brian Kelch, and Jeanne Hardy for feedback and discussions about this topic.